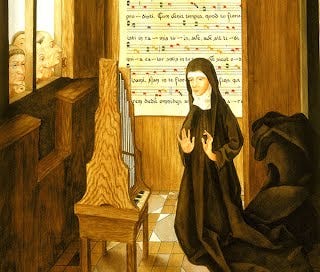

Today—Sunday, September 17th—is the feast day of St. Hildegard of Bingen. I relish any excuse to write about this medieval visionary, so a post on Hildegard’s theology of music is my way of remembering Hildegard on her feast day.

In addition to being an abbess, visionary, theologian, and preacher, Hildegard was a skilled composer of music. She wrote celestial musical scores as well as infused lyrical prose into her various theological works. In one of her books of visions—Liber Vite Meritorum, or the Book of the Rewards of Life—Hildegard uses musical language to describe biblical motifs. She paints the Virtues as harmonious, the resurrection of Christ as a symphony, and Mary’s joy as resounding with “harp and harmony.” Once, she wrote, “Oh Trinity, you are music, you are life.” Musical imagery and language infuse her theological reflections and teaching, contributing to the depth of her voice.

Honey Meconi, a scholar who analyzes Hildegard’s musical contributions, evaluates her musical emphasis as keeping with the standard medieval understanding of the cosmos: ”where music is the aural representation of this overarching order.” Music brings order to chaos—not in a uniform, monotonous manner—but in a way that sparkles with harmony. Think of Edenic paradise. The notes of a score are composed to incorporate many instruments in a beautifully harmonious way. There is an order to the symphony that is captivating to one’s ears. For Hildegard, music is a bridge from our chaotic earth to celestial harmony—or at least a glimpse of this harmony. Fascinating scholarship has been done in analyzing her musical compositions, but in this article I want to reflect on one of the richest aspects of her musical theology—her claim that the “soul is symphonic.”

Hildegard coined this phrase in a letter to an archbishop that contested his prohibition of Hildegard and her nuns from taking the Sacraments and singing the divine office. Hildegard and her nuns refused to dig up an alleged apostate man from their churchyard at his order and were subject to the prohibition of sacred activities for their refusal. The prohibition of singing the divine office provoked Hildegard most of all. She boldly wrote to the archbishop that if he did not allow her and her nuns to resume their singing, he might be subject to a place where there is no music at all—Hell. The archbishop lifted the interdict and Hildegard was able to enter the threshold of eternity with singing. She died a few months later.

According to Anna Silvas’s translation, Hildegard wrote that one’s soul

“has harmony in itself and is like a symphony. As a result, many times when a person hears a symphony, he sends forth a lamentation since he remembers that he was sent out of his fatherland (paradise) into exile.”

What does it mean that one’s soul is symphonic?

For Hildegard, a symphony provokes a longing for that which is just out of grasp in one’s present state. Encountering the beautiful order of a symphony prompts the listener to confront and lament her exilic state. This sounds bleak, but it is actually quite beautiful. The symphony acts as a glimpse into what was left behind in Eden as well as what will come in the celestial city. It invokes lamentation as well as eschatological hope. This can also be said of beauty as a whole—of which a symphony is a reflection. Paintings and sunsets as well as symphonies invite the observer to lament their fallen state that places their soul’s longings just out of reach while at the same time rejoicing in the eschatological promise of seeing Beauty in all Beauty’s fullness in the celestial city.

When Hildegard writes that the soul is symphonic, one thing she is referring to is the harmony that exists in the soul. Therefore, as the human person interacts with beauty in her life, her innate longing for harmony is heightened. Who else brings perfect order and harmony? This longing for harmony is a longing for God who is Beauty. The symphony reflects the harmony of God’s being. Hildegard was distraught at the thought of going without singing because music allowed her a glimpse of such a paradise.

A symphony is a show of beauty, and it is right that there is disappointment when the music fades. Our glimpse into paradise is just that–-a glimpse. For Hildegard, one’s soul is symphonic because its purpose is perfect harmony with God and music affords one a glimpse of temporal harmony that feeds this desire for union with God. Perhaps for you (the reader), it is a breathtaking sunset, natural wonder, or intricate painting that causes you to feel a heightened longing for something just out of reach. I believe the same principle applies yet the symphony provides a rich example as Hildegard demonstrates. Your soul is symphonic because it longs for harmony in a chaotic world.

There is so much more to explore regarding Hildegard’s theology of music. Everything said in this post could be expounded on for pages and pages. Conversations need to be had about what this theology of music and harmony does for human flourishing and the pursuit of that which is good and just in our present world. Additionally, her writings contribute not only to a theology of music but also to a theology of the arts—something I hope to reflect on in future posts. This article barely scratches the surface of all Hildegard wrote about theology and music! That being said, would you add any nuances to this post? What is your equivalent to the symphony (ie. When do you long most for something just out reach)?

Meconi, Honey. Hildegard of Bingen. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Silvas, Anna. Jutta and Hildegard : The Biographical Sources. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.